By Fitzpatrick, Mike | AP

NEW YORK (AP)Lou Carnesecca was the only person to wear it in the lengthy and legendary history of basketball in New York City.

Just a few weeks short of turning 100, the exuberant St. John’s coach, whose bizarre sweaters became a symbol of his team’s thrilling 1985 Final Four run, passed away on Saturday at the age of 99.

According to the institution, a family member informed it that Carnesecca passed away in a hospital with her loved ones by her side. According to St. John’s, the Hall of Fame coach won over generations of New Yorkers with his kindness and humor.

Big East Commissioner Val Ackerman expressed the conference’s profound sadness over the loss of Lou Carnesecca, a classic New Yorker and one of our greatest coaches ever.

The influence of Coach Carnesecca went much beyond the basketball floor. He shared his toughness, ferocity, and resilience with the conference he helped start, develop, and define. His accomplishments helped the Big East rise to prominence in collegiate athletics in its early years, and his conviction that basketball had the ability to define colleges is still ingrained in our culture. On the sidelines, Coach was a tactical genius who was also a father figure, teacher, mentor, master motivator, storyteller, ambassador, idol, champion, and friend. He was genuinely adored, and his impact on collegiate basketball, the Big East, and St. John’s can never be erased.

In his day, Carnesecca was a beloved city sports star, and his love for Little Looie remained unwavering in a busy town that had little tolerance for its owners, coaches, players, and executives.

He became the face of a university whose Queens campus arena would someday bear his name. He coached St. John’s for 24 seasons over two stints, qualifying for a postseason tournament every year. In advance of the 2021–22 season, a statue of him was unveiled. During a Q&A session with the school, Carnesecca was asked to define St. John’s and she said, “Home.”

He led St. John’s to 18 seasons with at least 20 victories and 18 trips to the NCAA Tournament there. He had 30-win seasons in 1985 and 1986 and finished with a 526-200 record there. Additionally, it served as the foundation for the Big East Conference’s success and the place where St. John’s became a charter member.

In a league that started in 1979 and soon established itself as one of the best in the country, he won coach of the year three times. Chris Mullin, Mark Jackson, and Walter Berry were some of his best players in those early Big East years.

Even though the NIT had long been a poor cousin to the NCAAs, Carnesecca led St. John’s to its sixth NIT championship in 1989. In 1992, the year he retired, he was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

At his induction, he wore a sharp suit instead of a sweater and declared, “I never scored a basket.” The players gave it their all. It is impossible to have a game without players.

He was a traditional coach with a foundation in principles. Carnesecca was a dynamic, whirling figure on the sidelines during it all, with his arms swinging, legs kicking, and shirt tails flying as he coiled up in frustration over a missed shot or a painful call. However, he never went too far with his pranks to the point of tossing chairs.

Carnesecca’s players were his entire world; he had a deep passion for the game and had spent his entire life in schoolyards, dilapidated gyms, and prestigious stadiums. He cherished the scent of perspiration and the sensation of rubber scorching as footwear touched a polished floor.

In a sport full of inflated egos, intense recruitment competitions, and a never-ending quest for the next contract, he remained the epitome of gentlemanly conduct. Former Big East commissioner Mike Tranghese once referred to him as one of the game’s titans and our soul and conscience.

In 1983 and 1986, Carnesecca led St. John’s to Big East Tournament victories. In 1979 and 1991, his teams advanced to the NCAA Tournament’s Elite Eight, and they were in the top 10 of the AP Top 25 for more than 70 weeks.At Madison Square Garden, a banner commemorating his 526 victories at St. John’s is suspended from the rafters.

He coached over 40 NBA draft selections, including 11 first-round selections, including Mullin, Jackson, and Malik Sealy.

Carnesecca never took himself too seriously in spite of all of that. He was always of the opinion that a glass of Chianti and some fettuccini with Bolognese sauce should never be put aside because of a difficult loss. He made friends everywhere he went, held clinics all over the world, and made toasts. He was there with a wisecrack in his raspy, breathy voice and a kind word. Even though his family originated in Tuscany, he was able to compete with the top comics from the Borscht Belt.

In an interview with the Hartford Courant, former UConn coach Jim Calhoun said, “I don’t know if there’s anybody else in coaching like him.” No one despises Looie, despite the fact that the Big East is hated. You like Looie if you enjoy basketball. You like Looie if you enjoy children.

Born on January 5, 1925, Luigi P. Carnesecca was the son of Italian immigrants. He was raised in East Harlem, Manhattan, above his father’s deli and grocery store. He supported New York Yankees players like Tony Lazzeri and Joe DiMaggio because he took his heritage seriously.

Following a stint in the Coast Guard during World War II, he was appointed coach at his high school, which is now Archbishop Molloy, a longtime basketball powerhouse. His old college, St. John’s, where he had played baseball on a team that advanced to the 1949 College World Series, hired him as an assistant in 1958, but he did not play varsity basketball there.

He spent eight seasons working for Joe Lapchick, and the Hall of Fame coach’s teachings on hard labor and humility lasted a lifetime. Later, Carnesecca would share with Mullin some advice he received from Lapchick: “Today is a peacock, tomorrow is a feather duster.”

Carnesecca stated, “I learned more when Coach Lapchick cleared his throat than I could have at any clinic.”

The 20-win seasons gradually piled up after he took over for Lapchick in 1965. Carnesecca, however, was not impervious to the pros’ allure after five years. Rick Barry was one of his players during his three years as coach of the New York Nets of the American Basketball Association.

Years later, in 1982–83, when his St. John’s team finished 28–5, Carnesecca thought back on his time in the ABA and the pressures of coaching at the collegiate level.

He claimed that pressure was the reason he lost fifty games while coaching professionally. I had no desire to get out of bed. This team might be coached by my mom.

His professional career was short-lived. Carnesecca knew he wasn’t meant to live there. He stated there was a limit to how many times he could deliver the same halftime address. In 1973, he went back to St. John’s.

Even if his city was no longer the recruitment hotspot of previous generations, winning seasons came quickly after. Prominent high school athletes moved to colleges with shiny arenas in the south and west, eliminating the need for New York’s commercial appeal to enhance their reputation.

When asked why he didn t expand his base in his search of players and venture beyond his city s five boroughs, Carnesecca knew he had plenty of talent in his neighborhood. He removed a subway token from his pocket, which is now a holdover from earlier generations.

“That’s my budget for recruiting,” he remarked.

By the 1984-85 season, Carnesecca and St. John s captivated New York, a throwback to a time when schools like City College and NYU mattered not only in the Big Apple but across college basketball. The Redmen their nickname years later changed to the Red Storm played tough, pulsating games at a packed Madison Square Garden against Syracuse teams coached by Jim Boeheim, Villanova teams coached by Rollie Massimino and Georgetown teams coached by John Thompson and led by Patrick Ewing.

At that point, The Sweater’s story began to take shape. Over the years, Carnesecca would recount his baffling entry into the world of fashion time and again like an embellished family tale.

Essentially, St. John s was getting ready for a road trip to Pittsburgh in January and Carnesecca was under the weather. The building would be drafty, and his wife thought it would be good if he wore a sweater. He found one that had been given to him by an Italian basketball coach. It was a brown pullover with broad turquoise stripes. It never made it into the pages of GQ.

It is ugly, isn t it? Carnesecca said.

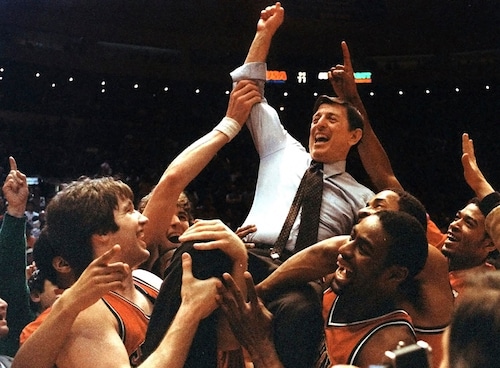

No matter. Mullin hit a winning shot at the buzzer, and the coach had his lucky charm. He stuck with the sweater. Along the way, St. John s ended Georgetown s 29-game winning streak and soared to a No. 1 ranking.

But there were also two lopsided losses to Georgetown during the 16-2 run with the sweater one when a grinning Thompson upstaged his popular rival by wearing a duplicate onto the court at a buzzing Madison Square Garden in what became known as The Sweater Game, which drew a massive television audience in February 1985.

His luck exhausted, Carnesecca eventually put the pullover away. He then went with a tan, snowflake number for the NCAA Tournament. St. John s defeated Southern, Arkansas and Kentucky before a victory over North Carolina State in the West Regional final sent Carnesecca to the Final Four.

When I m going to my grave, he said, this I ll remember.

St. John s headed to Lexington, Kentucky, along with two Big East compatriots Georgetown and Villanova and Memphis. St. John s stuck with Georgetown in the semifinals, down 32-28 at halftime. But the Hoyas pulled away to win 77-59, holding Mullin to eight points.

I think we tried everything, Carnesecca said of Georgetown, which then got upset by Villanova in one of the sport s great championship games.

After he retired, Carnesecca was succeeded by a parade of coaches at St. John s, Mullin among them. Even into his 90s, some three decades out of coaching, Carnesecca would make his way to The Garden when the Red Storm were there. His gait may have been tentative but his mind and wit nimble, the crowd roaring when the jumbo screen panned in on him. The coach was at home.

It s going to be very difficult to put the ball down, but the time has come, he said at his retirement when he was 67. There are two reasons, really. I still have half of my marbles and I still have a wonderful taste in my mouth about basketball.

The school said Carnesecca leaves behind his wife of 73 years, Mary, as well as daughter Enes and son-in-law Gerard, a granddaughter, and a niece and nephew in addition to extended family.

___

A previous version of this story corrected Carnesecca s record at St. John s.

___

Fred Lief, a retired Associated Press sports writer, was the principal writer of this obituary. Former AP Sports Writer Paul Montella contributed to this report.

Note: Every piece of content is rigorously reviewed by our team of experienced writers and editors to ensure its accuracy. Our writers use credible sources and adhere to strict fact-checking protocols to verify all claims and data before publication. If an error is identified, we promptly correct it and strive for transparency in all updates, feel free to reach out to us via email. We appreciate your trust and support!

+ There are no comments

Add yours